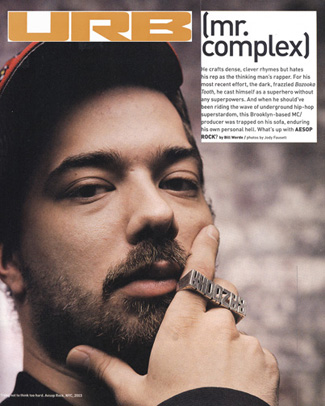

MR. COMPLEX

He crafts dense, clever rhymes but hates his rep as the thinking man's rapper. For this most recent effort, the dark, frazzled Bazooka Tooth, he cast himself as a superhero without any superpowers. And when he should've been riding the wave of underground hip-hop stardom, this Brooklyn-based MC/producer was trapped on his sofa, entering his own personal hell. What's up with Aesop Rock?

Brooklyn, 3 p.m., the end of summer. Aesop Rock's – Ian Bavitz by birth – apartment is a shit-hole. It's not the apartment or the neighborhood. Rather, his brownstone in this mostly hip enclave of Brooklyn is structurally gorgeous, with high ceilings and airy rooms. It's just that personal maintenance doesn't seem to high on the guy's list.

His living room is a couch, a little table and a TV, all buried by what appears to be the after-effects of a hip-hop cluster bomb. Old newspapers and rap magazines are strewn around the perimeter, and the table, piled high with matchbooks and scraps of paper and pack after pack after pack of cigarettes, some empty and crumpled, some with a few smokes left, forms an apex amid piles of clutter and trash. Pro-Keds with fat laces sit askew, packs of EZ-Wides and empty Snapple bottles litter the floor. Crumbs are scattered about, along with plastic cups (some converted to makeshift ashtrays) and clothing labels that say "2XL" and stick to your feet as you walk. In one corner is his recording gear – an Ensoniq keyboard, a Roland 303, a G4 with ProTools, a busted turntable. The walls are barren but for one corner with posters of old tours and albums – mostly from his label, Def Jux – and a couple of shelves of Zoids and Bionical figurines, and a talking Master P doll.

If Bavitz's apartment seems a bit jumbled and dense, well, that wouldn't be so different from his new album, Bazooka Tooth, and it wouldn't be so different from his life since the end of 2001. To the casual observer, it might seem that Aesop Rock should have been on top of the world. Labor Days, his first album for indie hip-hop's premier label, Def Jux, was out and doing well. "Daylight," the strongest single from the album, with its happy-sad, '70s AM rock backing track and memorable, upbeat hook ("All I ever wanted was to pick apart the day/Put the pieces back together my way"), had become a bona fide underground hit; the album would go on to sell some 40,000 copies. Magazines fawned over the rapper's unique, elastic delivery and his seemingly encyclopedic knowledge of culture, delivered one clever couplet at a time. Yet, while this transpired, Ian Bavitz was in his own personal hell.

The rapper doesn't like to discuss it. He stares off at the television and mumbles, taking endless drags from his cigarettes. Around the time the twin towers went down, around the time his girlfriend of several years split for the west coats, around the time Labor Days came out and expectations were high, "I had some kind of anxiety attack," he says. "It was some real shit. Luckily, there were some people around me who gave a shit, who literally took me into their hands, started making phone calls, getting me help."

As much as Bavitz may not like to discuss personal details, Aesop Rock can't help but wax poetic over the fodder of life; the one thing the rapper can always find in his apartment is his mini digital recorder, and he's constantly recording rhymes and ideas. Bavitz rapped most directly about his difficulties on "One of Four," a hidden track at the end of the Daylight EP, the last thing he released before Bazooka Tooth. The song explicitly details the four people who Bavitz says he owes his life to, the four friends who were there when he needed them. Included in the four was El-P, rapper and owner of the Def Jux label. "I could live to be 1,000 years old and never repay them," Aesop raps at the track's beginning. "In August of 2001 my seemingly splinter-proof brain bone scaffolding exploded…I'd be lying if I said all of this made even the slightest fragment of sense to me/That's real/Simply put, I don't know what happened or what's still happening/I literally feel like I'm teetering on the blunt edge of my sanity."

Bavitz went weeks at a time without leaving his couch; a simple walk to the deli for smokes could reduce him to extreme desolation. Meanwhile, the Who Killed the Robots tour, slated to be Aesop's introduction to America alongside Mr. Lif and Atmosphere, intended to promote his new album, went on without him.

"Before I really understood what was going on, I was worried about the effects of him canceling the tour," says El-P, Bavitz's boss as well as friend. "Once we knew what was happening, we let him know that it was more important that he was OK than for him to be ambitious."

Bavitz never stopped making music, though. He invested almost anything he made from Labor Days into his studio gear and continued to experiment with production. And he channeled the dark days of his life into beats and rhymes that, likely, the world will never hear. "I leave those decisions to my artists," says El-P of that material. "If it was up to me, some of it might surface. There was some pretty monstrous stuff there."

Bavitz was born in Long Island in 1976. His most significant early musical influence was his older brother, who turned young Ian on to Run-DMC's Raising Hell and the Beastie Boys' Licensed to Ill, both of which were soon confiscated by their mother. "She walked into my brother's room and he was like, 'I did it like!/I did it like that!/I did it with a waffle-ball bat!' and that was pretty much it," he recalls.

Bavitz started rhyming for his friends and occasionally recorded his raps on his older brother's four-track. "There was hip-hop all around in high school," he says. "We were skateboard kiss taping [NY radio DJs] Stretch and Bobbito." After high school, he went to Boston University to study paining. "After I graduated, I was trying to make it with music and trying to paint and I ended up half-assing everything," says Bavitz, who had moved back to New York.

But he was making himself known in New York's underground. As a white guy, Bavitz recalls, "You had to do your thing if you didn't want to get made fun of." He says that when he was young, he never strove to be a rapper: "I was the white kid. I didn't think it was an option. You'd have these dreams of being the only white kid in a room and people being like, 'Oh shit, he's good.' Anybody who says they didn't have that thought is lying."

Bavitz isn't keen on the "white rapper" questions, though. "It's almost like someone asking for an excuse," he gripes. "'What's your excuse for being a white rapper?' What do you want me to do, apologize? I'm sorry, but I feel like I was born to be a rapper. I put my legwork in like anyone else."

Music for Earthworms was his first self-release. The album still circulates, thanks to CD burns and downloads, but he sold only 200 copies. "I got tired of cutting covers at Kinko's," he explains. With his follow-up, Appleseed, he made more of an effort. "Cats would call my house and be like, 'I got your number from this guy, who knows this dude, and I want 10 copies for my store.' I never expected to have one fan. When I started selling tapes and cats were interested, I was shocked. Selling 2,000 copies was like going platinum."

These early albums found their ways into the hands of Robert Curcio, owner of the then-fledgling Mush Records, and Aesop Rock put out his label debut Float in 2000. The album was literally crammed with music. "Twenty incredibly pretentious songs," says Bavitz. But the album established the rapper as a unique vocal talent, grouped with the likes of Del the Funkee Homosapien and Kool Keith. And to Bavitz's apparent chagrin, it earned him a literary reputation.

"6B Panorama" on Float found him describing the view from his balcony, writing of "a bus stop of commuters waiting to have their souls towed off to work," and "a black man with a horn and a will to make you sit and listen to it." A trip to dirtyloop.com, the site for Mush records, reveals interview after interview of Bavitz explaining how he's "not that smart." Curcio says he's not sure why Bavitz is so uncomfortable with his status as the thinking-man's rapper. "All you ever hear rappers saying, 'Look at me: I'm dope,' Ian comes out with "This fallen angel could stitch a wing with a shoestring," says Curcio, citing a line from Floats title track. That's Ian's way of saying, 'Look at me; I'm dope.' He should be proud of being poetic like that."

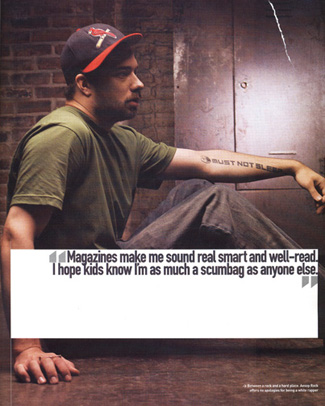

Some of Bavitz's discomfort may be chalked up to misrepresentation; he's a poet, but no scholar. The one thing you won't find in the fallen piles of his life and abode is a book. "Journalists get offended I don't read," says Bavitz, who claims to have not cracked a book in 10 years. "Magazines make me sound real smart and well-read. I hope kids know I'm as much a scumbag as anyone else. I take my time to write and I take my art seriously. But it's weird to be put on a pedestal. I still said the same shit. Does it mean less that I didn't bit it out of a Kafka novel?" But then, what literate makes Kafka references?

"His language and prose, when it comes out, it's almost scary that they can come out of someone who doesn't have a serious academic background," says El. "He's one of those rare natural writers. He grew up watching TV, writes like an accomplished poet, and can still sound like a hardcore rapper."

To promote Float, Bavitz hooked up with Kathryn Frazier, a publicist who was also promoting Def Jux; Def Jux rappers Cannibal Ox had also become fans of Aesop's, so it was only a matter of time before El-P was turned on to Aesop Rock. Bavitz continued to work at a SoHo art gallery, "setting up shows and unpacking shit," until Labor Days came out in September 2001. "El was like, 'This shit is moving; you have to go on tour,'" recalls Bavitz. "I was like, 'I have to work,' and El said, 'You make music now. That's what you do.'"

The first video from Bazooka Tooth is for the single, "Freeze," in which Aesop Rock spits literal and figurative fire, animated flames trailing from his lips as he drops rhymes of paranoia and despair. "Bazooka Tooth was my post-meltdown character," says Bavitz. "A superhero with no super powers. A bazooka comes from my teeth and just blows shit up."

For the first time, Bavitz produced much of the album himself. He says he's aware it's a darker work. "If the beat sounds frazzled, it's probably because I was frazzled," he says. Much of the record is consumed with the problems of the world, as on "Babies with Guns" ["Diaper snipers having clock-tower fun/Misplace the bottle might catch a bad one"], or his own neurosis. "Cook It Up" is a hilarious scat-funk effort in which the rapper appeals to the ladies, Bavitz style: "I'm clinically bonkers and hate just about everyone God's great earth offers/I won't be getting dressed up to impress your family, dear/and if I can't wear jeans and sneakers then I won't be landing there." Later comes the falsetto chorus: "There ain't no strings attached/But if you love television and manic depression/Get a carton of cigarettes/We can make it happen." Elsewhere, El-P and Aesop tag-team on "We're famous," a verbal evisceration directed at hip-hop wannabes.

"I'll probably lose fans with this record," says Bavitz. "But I can't cater to my fans. Some of these kids really rely on me, and I know 'cause they tell me. It's dope to know those fans are out there, but at the same time, I can't make music for you. What if I'm going through some other shit, you know?" Bavitz says he sees this album as make it or break it. "I'll hit 100,000 or people will decide Aesop isn't cool anymore. If they tell me the record sells 20 copies in the first six months, I'll go get a job."

Bavitz's boss says that's crazy talk. "I don't see albums as make or break, ever," says El-P. "I want you to look back on 10 albums, and see where Aesop Rock was at different times in his life. He's fooling himself if he thinks he doesn't have a long career in front of him. He's the type of cat who thinks everyone around him – his friends, his crew, his label – are going to suddenly stop fucking with him. I think slowly he's realizing that's not going to happen."

Those close to Bavitz say he's doing much better now. He's continued to shell out the big dollars for therapy. He started going to the gym for the first time in his life. A national tour is planned, two weeks on and two weeks off, to give him regular breaks from the demands of the road.

After a few long hours of talking, Bavitz heads down the street a few blocks to El-P's place, ground zero for the whole Def Jux family. Aesop's manager is manning the grill for a barbecue, and the soft glow of torches illuminates the worn bricks of Brooklyn in El-P's backyard. El-P drags out his kiddie pool to fill it and C-Rayz Walz hops in and tests its ability to abide by various sexual positions. "Yeah, that'll work," he says, smacking the ass of some undoubtedly fine imaginary hottie. Def Jux sound engineer Nasa busts on Metro of SA Smash for drinking "parent' beer" [Becks] and someone pulls out a blunt; the sweet smell of mingling cigar papers and weed wafts about. Aesop sits and laughs and seems at home.

"I don't want to be 'the Brooklyn Jesus' or 'the plain-clothes prophet' or whatever else I've been called," he says. "I got a fistful of friends who are the dopest rappers in the world, and I got a TV. That's it. I just want to go home and make a beat."

BILL WERDE